At some point this year, and as early as May, the seven justices of the Illinois Supreme Court will file into their courtroom in Springfield and hear arguments in the case People v. Ringland.

The justices will hear about Cara Ringland’s decision in 2012 to hop in a U-Haul van loaded with roughly 100 pounds of marijuana and drive it eastward from California.

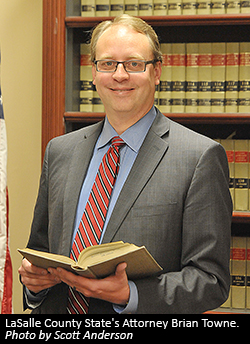

They will hear about Brian Towne’s decision in 2011 to addend his LaSalle County State’s Attorney’s Office with an independent police force tasked with patrolling Interstate 80, arresting drug runners like Ringland and seizing cash.

And the justices will make their own decision regarding a seemingly simple question: Does Illinois law allow prosecutors like Towne to hire special investigators who act like police and make arrests?

What the justices won’t necessarily hear is what is detailed in this story, a follow-up to an article published in December and the result of a monthslong investigation following the convoluted money trail created by Towne’s State’s Attorney Felony Enforcement Unit, or SAFE Unit.

The investigation identified four sections in two Illinois laws, the Cannabis Control Act and the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act, which the SAFE Unit may have violated. A fifth is at issue before the Supreme Court. (This Chicago Lawyer chart breaks down these potential violations.)

The investigation centers around two LaSalle County bank accounts controlled by Towne: one that received portions of civil forfeitures made by the SAFE Unit and another that received drug fines paid by defendants arrested by SAFE. Combined, the accounts grew by more than $1 million since the controversial program’s 2011 beginnings, according to a review of documents obtained by Freedom of Information Act requests.

Controversial spending from Towne’s civil forfeiture fund — including nearly $100,000 spent on traveling to drug law enforcement conferences and $17,000 in per diem payments made to him and his office’s employees — was detailed in a previous article.

The potential violations detailed in this article involve Towne’s use of civil forfeitures to fund the SAFE Unit; the way the SAFE Unit transferred forfeited funds to other government bodies; and ways Towne spent money collected by civil forfeitures and drug fines — spending that at times appeared to benefit him politically, such as a county-funded college scholarship he created and named after himself.

These possible violations emerged from the confluence of at least three factors: a lack of oversight at multiple levels of government; a set of state laws that Towne argues are vague; and his admitted habit of stretching those laws as broadly as he can to benefit his constituents. If his actions don’t follow a word-for-word reading of the law, he says, maybe that’s not the way the law was intended to be read.

“I think I’m interpreting the statutes accurately but effectively for my community,” he says. “One might have to believe that the vagueness of the [laws] very well could be intentional to give our community’s leaders the leeway to improve their communities based on their knowledge of the area they are elected within.”

The first potential violation stems from Towne’s use of money collected from drug fines. Last year, Towne asked for and received approval from the LaSalle County Board to donate more than $50,000 to organizations that solicited him personally for funds the county received from drug fines, according to documents obtained through FOIA requests.

Towne has directed the donations, since 2011, to organizations including an adult flag football league, sports programs at a Catholic school, an adult baseball tournament, a middle school seeking funds for an eighth grade trip to Washington, D.C., and a college baseball team coached by an assistant state’s attorney in Towne’s office, among others.

The Cannabis Control Act says drug-fine money allocated to state’s attorneys must be spent “in the enforcement of laws regulating controlled substances and cannabis.”

Towne’s policy, he admits in an interview, is much looser.

“I guess you can’t go by the adage of ‘it’s right because it’s always been done that way,’ ” says Towne, who has worked in the state’s attorney’s office since 1992 and was appointed to the top job in 2006. “I can certainly tell you that all of my predecessors have utilized drug fund money at their discretion to improve the quality of life in LaSalle County. And that’s kind of the motto that I adhere to.”

Some residents have criticized this spending and urged Towne to direct the funds to drug rehabilitation programs, which the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act specifically allows state’s attorneys to fund.

In the last decade, LaSalle County has struggled with a ballooning heroin problem. It was one of five Illinois counties with more than 20 drug overdose deaths per 100,000 people in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Last year, there were 26 drug overdose deaths in LaSalle County, with 13 at least partly attributed to heroin, according to records obtained from the coroner’s office.

Glenn Sechen, a longtime Cook County assistant state’s attorney who is now in private practice, reviewed SAFE Unit financial documents and portions of the Cannabis Control Act and Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act on behalf of Chicago Lawyer. He says multiple aspects of the unit were “problematic,” including Towne’s penchant for county-funded self-promotion.

“It’s empire building,” Sechen says. “Frankly, it’s a shame that this happened.”

An arrest leads to a seizure

On Feb. 23, 2012, David Allen Fink Jr. was headed westbound on Interstate 80 in his 2004 Ford Ranger pickup. The California resident picked a bad time to roll through LaSalle County with 11 marijuana cigarettes in his car.

Less than six months earlier, Towne created the SAFE Unit and began targeting drivers with California and Arizona license plates. Dan Gillette, a retired Illinois State Police officer who now worked for the SAFE Unit, clocked Fink traveling 75 mph in a 65 mph zone and pulled him over.

Before Gillette finished speaking to Fink at his car window, an officer from the Spring Valley Police Department arrived with a drug-sniffing dog, Hera. Within moments, Hera buried her nose in the seam of the driver’s side door and took a seat, alerting officers to the presence of marijuana. Shortly thereafter, the officers seized the marijuana and $50,000 in cash from the vehicle, according to the officers’ reports of the arrest.

Fink did not contest the forfeiture, and no charges were brought against him.

.jpg.aspx)

But Fink’s arrest is an example of the dual purpose Towne says he hoped the SAFE Unit would serve: It got drugs and money off the street.

And it did so quite successfully, racking up 66 drug convictions, according to documents received through a FOIA request. SAFE also led to more than 50 civil forfeiture cases, 23 of which were not tied to a criminal charge, according to a review of court documents by a Peru-based attorney, Julie Ajster.

The SAFE Unit is on hold pending a Supreme Court ruling.

The SAFE Unit was so effective at seizing cash and eliciting drug fines that it appears to have paid for itself.

Bank records from the county forfeiture fund show it paid for the SAFE Unit’s vehicles, guns, office furniture, computers, uniforms and the cost of attending conferences that Towne says the officers required to stay abreast of the latest threats in highway interdiction work. Gillette and another retired state police officer made more than $140,000 in pre-tax salary over four years, records show.

This is possible evidence of the second of four sections in Illinois law the investigation found SAFE may have violated.

The second sentence in the Illinois Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act reads: “While forfeiture may secure for state and local units of government some resources for deterring drug abuse and drug trafficking, forfeiture is not intended to be an alternative means of funding the administration of criminal justice.”

In an interview, Towne does not deny the SAFE Unit is funded by forfeitures. He argues, however, that the state’s budget problems justify his use of seized funds to bankroll SAFE.

“I appreciate and respect what the statute says, although one could argue that that is somewhat vague or ambiguous language,” Towne says. “And what it boils down to for me, is that with a state that’s running out of money … everything I can do consistent with my goals to support law enforcement, drug prevention and drug awareness, I will continue to do to the best of my knowledge and ability.”

The third potential violation kicks off from where the story of Fink’s arrest ends: at the beginning of the SAFE Unit money trail.

The checks are cut

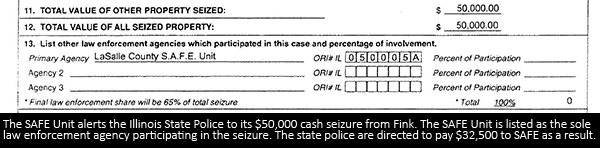

As protocol dictates whenever a civil forfeiture occurs, the SAFE Unit officers filled out a form notifying the Illinois State Police they had seized $50,000 from Fink. The form is required because the state police act as a kind of escrow service for civil forfeitures throughout the state. They hold on to the cash and distribute it when the civil court case is completed. For this, they receive a 10-percent cut of all successful forfeitures.

The forfeited funds statute breaks up the rest in this way: The state’s attorney in the county of the seizure gets 12.5 percent; the state’s attorney’s appellate prosecutor gets 12.5 percent; and the law enforcement agency that conducted the seizure gets the lion’s share — 65 percent.

This financial arrangement caused the SAFE Unit to come under scrutiny early on. Some defense lawyers used Towne’s financial incentive to seek special prosecutors in their defendant’s SAFE cases.

“There is an inherent conflict of interest when the entire case, from inception to prosecution is in the hands of one individual, whose interest it is to bring in all the money he can,” Robert Campbell, a Chicago attorney, wrote in an unsuccessful petition for a special prosecutor.

But Towne, giving witness testimony in multiple cases, always denies his office received the 65-percent share of forfeited funds — insisting the money went to the city of Spring Valley, not SAFE.

“The arrangement that we have with the Spring Valley Police Department and subsequently the LaSalle Police Department is that they are considered the law enforcement agencies for receipt of those funds. I only receive 12.5 percent,” Towne in 2013 told Stephen Komie, a Chicago attorney who represents Ringland in the case before the Supreme Court, according to a transcript of Towne’s testimony.

On the form notifying the Illinois State Police of the forfeiture, there is a section that allows multiple law enforcement agencies to be listed as participating in the seizure. This allows cooperative police units like SAFE — a tag team consisting of the LaSalle County State’s Attorney’s Office investigators and the Spring Valley Police Department — to split up their portion of the forfeiture based on their involvement.

But the form for Fink’s $50,000 seizure only lists one arresting agency: the LaSalle County SAFE Unit. This appears to be the case for all the forfeiture forms SAFE filed.

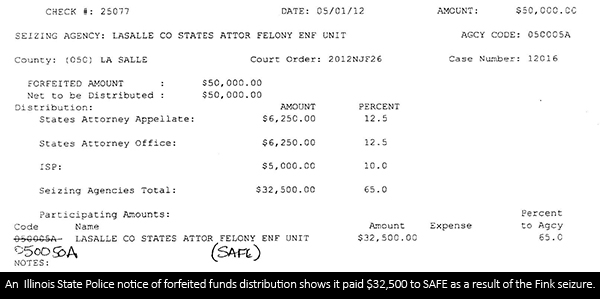

As a result, when the Illinois State Police divvied up Fink’s $50,000, they wrote three checks: one for $6,250 to the LaSalle County State’s Attorney’s office; one for $6,250 to the state’s attorney’s appellate prosecutor, where Towne serves as chairman of the board; and one for $32,500 to the LaSalle County State’s Attorney Felony Enforcement Unit — not Spring Valley.

Towne has now told Komie one thing under oath and the Illinois State Police something else entirely.

The checks are deposited

And yet, Towne is being truthful when he says, “I only get 12.5 percent.”

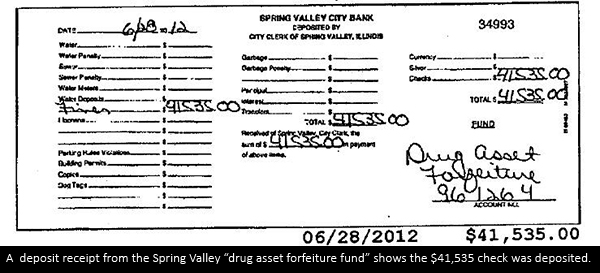

That’s because his office signed over the checks the Illinois State Police sent SAFE for the arresting agency’s 65-percent share of the forfeited funds to Spring Valley. The $32,500 resulting from Fink’s seizure, for instance, was deposited in a Spring Valley drug asset forfeiture fund, records show. (View more of these documents in this Chicago Lawyer infographic.)

In total, the SAFE Unit transferred to Spring Valley $528,567.87 worth of checks made out to SAFE by the state police from June 2012 to August 2015, Illinois State Police documents show and Spring Valley bank account records confirm.

Chicago Lawyer explained this arrangement to David B. Smith, an Alexandria, Va.-based lawyer who is known nationally for his work on civil forfeiture laws. “I’ve never heard of anything quite so complicated,” Smith says. “I just don’t like the smell of it. And, again, it just shows how money drives this machine.”

When asked multiple times why the SAFE Unit listed itself as the arresting agency on forms to the Illinois State Police — despite his claim that he had no intention of keeping the arresting agency’s portion of the funds — Towne provides unclear responses.

“The SAFE Unit was the arresting agency,” he says. “[It was] the beneficiary, for lack of a better term, of the monies received in the forfeiture. We have our own ORI number, our own arresting agency number. But in the interest of, if nothing else, so all of the money wasn’t just handled by one agency, the check would come to us … and the chief of police of Spring Valley was then responsible for maintaining the account and distributing the funds equitably.”

Towne then says he could call Kevin Sangston, the Spring Valley police chief, to ask for funding: “If we had anything that we needed — something that was strictly law enforcement — there’s a good chance I’d call Kevin Sangston and say, ‘Hey, the SAFE Unit needs a piece of equipment.’ ”

When asked if he misled the state police regarding SAFE’s status as the arresting agency, Towne says, “I certainly don’t think we were misleading the state police. The state police knows everything there is to know about SAFE.”

Chicago Lawyer provided the Illinois State Police documentation of the forfeited-funds checks SAFE sent to Spring Valley. Lawyers at the state police flagged the response the agency drafted to a series of questions and forwarded the documents to the Illinois Attorney General’s office, according to Matthew Boerwinkle, the state police’s chief public information officer.

In early February, a spokesperson at the Attorney General’s office said it had “not yet received” a request to investigate the issue from the state police.

The deposits are questioned

Lawyers for the state police may have flagged the documents because the transfers of forfeited funds are the third potential violation of state law this investigation found.

A section of the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act allows law enforcement agencies to share forfeited funds. In order to do so, however, the agencies must meet a number of requirements.

Among others, the municipality receiving a share of the funds — in this case, Spring Valley — must have a population of more than 20,000 people; the seizures must occur within that municipality; and the municipality must have a contract to provide at least $1 million in police services per year.

Spring Valley has a population of around 5,000 people. It isn’t in LaSalle County, where the SAFE Unit operated and where the seizures occurred; it is in neighboring Bureau County. And the contract between the SAFE Unit and Spring Valley police makes no mention of the value of police services Spring Valley agreed to provide.

In other questionable transfers of funds, the city of LaSalle, which has nearly 9,500 residents, received $99,095.51 from Spring Valley, Sangston says in response to a FOIA request.

And records show Ottawa, a town of about 18,500 people, received $37,604.12 in the form of two checks from Spring Valley. Shelly Munks, the Ottawa clerk, says she cannot provide a written agreement between the town and SAFE.

“I have nothing that delineates why it was split up the way it was. No agreement. We have nothing. That’s just what they gave us,” she says.

When asked if his sharing of funds with Spring Valley violated Illinois laws, Towne began to describe the SAFE Unit and the role of the Spring Valley police. He then concludes: “I’m not sure if the section you just read to me was completely applicable to SAFE when we created the unit.”

The deposits are spent

As the money seized by Towne’s SAFE Unit officers took a scattershot route to one bank account, another account steadily filled up from a more direct source: fines paid by drug defendants.

Take Joseph Massamillo, for instance. The 69-year-old Arizona resident was stopped by a SAFE officer on Dec. 7, 2012. The officer found about four pounds of marijuana in his car, and Massamillo was charged with intent to deliver. This resulted in a deposit made to a drug fine account in June the next year worth $9,118.35, records obtained through a FOIA request show.

The LaSalle County budget refers to the account where Massamillo’s money went — and all other drug fine payments in the county — as “Fund 25.” With Towne’s SAFE officers on the highway, Fund 25 swelled, bringing in $495,760.72 from November 2012 through December 2015, according to records obtained through a FOIA request. (The State’s Attorney’s office says records of deposits from prior to November 2012 are unavailable because the county switched its accounting program at that time.)

The county board controls the newly-flush Fund 25. But records indicate Towne directs the spending. This is the spending this article previously identified as the first potential violation.

Some residents of LaSalle County knew Towne had money to spend — and sent him letters requesting money from his drug fund. Towne then asked the county board to approve the spending, records show.

Randy Gunia, the athletics director of LaSalle-Peru Township High School, says in an interview Towne’s drug fund was “one of the good things about living in this area.” Perhaps with that in mind, Gunia sent Towne a letter in June last year asking for donations “from your drug enforcement funds” to help alleviate the cost of a new state athletics by-law requiring random drug testing of athletes.

The letter ends: “We would obviously promote your contributions and your efforts to assist with the IHSA clean athletics policy through multiple media sources.”

The letter soliciting money from Towne was one of more than a dozen such letters obtained via a FOIA request of Fund 25 expense and deposit receipts. There is also a record of a $500 check being cut in response to the request.

When asked about the letter, Towne laughs and says, “I don’t really know what that meant. I certainly didn’t do it to be promoted in that fashion and I don’t believe I was promoted in that fashion, to be honest.”

There are other instances where Towne’s use of the county funds could be considered more obvious self-promotion, even if the opportunities weren’t presented as a quid- pro-quo.

Towne used Fund 25 to pay for a $500 scholarship given to a LaSalle-Peru High School student who wants to work in law enforcement. The scholarship, announced in a local newspaper article that ran with a photo of Towne, was named The Brian Towne/ Nancy Kochis Scholarship for the Legal Profession.

The LaSalle Softball League president sent Towne a letter asking him to purchase shirts for 100 girls between the ages of 6 and 18. The shirts, as the president describes them to Towne in the letter, “will have a clinic design on the front, a quote on the back, a drug-free icon on one sleeve and your logo on the other.” Towne requested and received approval to spend $1,200 on the shirts, a county invoice shows.

In another instance of questionable spending, Towne procured $500 from the drug fund to help a college baseball team attend a spring training camp. The team is coached by one of his assistant state’s attorneys, Jason Goode, who wrote Towne a letter requesting the funds.

Towne, however, says he has not spent money from Fund 25 to promote himself as a politician.

“I believe that if we can provide alternative ways for our youth to be engaged, that they will avoid drug usage,” he says. “… When I give money to a program to help build that program or support that program, I don’t do it to get elected or re-elected. I do it to make that a better program.”

Often, Towne’s campaign fund makes donations to the same community organizations that receive funding from Fund 25.

In the quarter from July to October last year, expense records from Citizens for Towne State’s Attorney show donations worth $1,000 to St. Bede Academy; $200 to LaSalle-Peru high school; and $200 to the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Department.

In August during that same quarter, Towne received a letter from the athletic director of St. Bede Academy “formally requesting the sum of $4,000 from your drug fund” to pay for the school’s football and volleyball programs. Records show the funds were shortly thereafter distributed from Fund 25.

In October, Towne was asked to donate $1,500 to a mentor program at LaSalle-Peru high school. A check in that amount was sent from Fund 25. And in 2014, Fund 25 paid more than $6,000 to purchase weight-lifting equipment for the LaSalle County Sheriff’s Department.

The spending is rationalized

In theory, the LaSalle County Auditor should know where the money deposited into Fund 25 comes from and what laws govern its spending. In practice, that is not the case.

When Chicago Lawyer asked the auditor, Jody L. Wilkinson, for a description of the fund and what statutes govern its spending, she provided a portion of the forfeited funds statute. Fund 25 does not receive forfeited funds, however. It takes in drug fines, the spending of which is governed by the Cannabis Control Act.

The Cannabis Control Act says drug fine money should be spent “for use in the enforcement of laws regulating controlled substances and cannabis.”

Presented with the spending Towne directed from Fund 25, Wilkinson says it was justified because it was for “charity.” That concept is similar to Towne’s interpretation of the statute, which he says is to “improve the quality of life” in LaSalle County.

“I think it’s to Brian’s credit that he’s handing that money out to children or programs involved in helping students or to municipalities to fight the war on drugs,” Wilkinson says.

In regard to the $500 sent to assistant state’s attorney Goode’s baseball team, Wilkinson says, “Jason Goode would have firsthand knowledge if there were funds available to give to charity.”

An article published in the January issue of Chicago Lawyer raised questions about the fourth possible state law violation regarding the SAFE Unit: how it spent money acquired by cash seizures.

An analysis of expense records obtained through a FOIA request shows roughly one-fifth of the spending from Towne’s forfeited funds account — more than $95,000 — was spent on travel expenses for law enforcement conferences. That total includes more than $17,000 in checks made out to him or his employees for per diem payments while traveling.

The forfeited funds statute uses the same language as the Cannabis Control Act to direct a state’s attorney’s spending: It must be spent enforcing laws regulating controlled substances. But it also adds this phrase: “Or at the discretion of the state’s attorney, in addition to other authorized purposes, to make grants to local substance abuse treatment facilities and half-way houses.”

As of May 2015, there was no record Towne donated money specifically to a substance abuse treatment facility or half-way house from his forfeited funds account.

The spending is questioned

At the moment, Towne is running his first contested campaign as state’s attorney. Karen Donnelly, who worked in Towne’s office while studying for her law degree, is running as a Republican challenger to the Democrat Towne.

Notified about Towne’s Fund 25 spending, Donnelly calls it an unfair political advantage.

“These donations he is making — without any oversight whatsoever — he is making for campaign purposes and his own politics,” Donnelly says. “And I have a real problem with that.”

If elected, Donnelly says she would disband the SAFE Unit, and she would not use money from the drug fund or civil forfeitures to make donations to private organizations; instead, she would work to use the money to create a specialized drug court and to have “boots on the ground” fighting the county’s heroin epidemic.

“He wants everybody to see the donations and say, ‘This is the great and powerful Mr. Towne,’ ” Donnelly says. “It hurts me to say that because I’ve known this guy since he got out of law school. But I think he’s become very complacent, and he thinks he can do whatever he chooses to do. And obviously the money says it all. I think the taxpayers need to hear this.”

One local taxpayer who was not pleased to hear about Towne’s drug fine spending was Debbie Hallam.

Hallam’s son, Dustin, started acting strangely his senior year of high school, eventually attempting to drop out just a month before graduation. Hallam thought he was taking painkillers. She drove him to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. When the meeting ended, Dustin got in the car with tears in his eyes. He told his mother he had something to confess.

“I’m a monster,” he told her. “I’m addicted to heroin.”

At her son’s funeral a year later, Hallam would see her nearly two-year-old grandson leap from her arms into his father’s open casket. Dustin died of a heroin overdose at the age of 20. Months later, his mother began a nonprofit that helps drug addicts get into rehabilitation programs. Last year, she says she placed 120 people in rehab, many times paying fees up to $400. She raises her own funds — $10,000 last year.

“We need more maintenance and treatment options,” Hallam says. “We have to travel two hours away to get them into rehab. There is nothing in this area.”

Since SAFE’s 2011 inception through October 2015, deposits into two Spring Valley bank accounts — referred to as “drug asset forfeiture fund” and a “seizure account” — totaled more than $1.7 million, according to bank records obtained by Chicago Lawyer. As of October, those accounts held more than $330,000.

Last year, Fund 25 brought in more than $40,000 in drug fines. And the state’s attorney’s drug forfeiture fund has typically held a balance of more than $140,000. The law specifically allows state’s attorneys and law enforcement officials to spend forfeited funds on rehab programs and halfway houses.

Towne, however, denies his past spending could have been directed towards more effective drug prevention or drug treatment programs. He stands behind the $500 payment to his employee’s baseball team, saying it was justified because it provided an “alternative activity to unlawful behavior.”

When asked about his efforts to address the county’s heroin epidemic, Towne says, “The fund is not broke. Anybody who makes contact with me with a genuine interest in one of those three areas — drug enforcement, drug prevention or drug awareness — who can present to me why their program falls in those categories and is a good, established program, I’d be happy to give money to them.”

After speaking with this reporter in late January and learning of Towne’s donations to other organizations, Hallam asked Towne for a donation to her foundation, Dusty Roads. Towne responded to her letter, she says, by agreeing to give her $5,000.

She may not be the only one contacting him.