As is the case with anything that is nearly 120 years old, the history of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange contains controversy. There have been swindlers and there have been manipulative traders.

And then there is Vince Kosuga.

To this day, Kosuga remains the Big Kahuna of infamous traders, thanks to his handiwork in the onions futures market in 1956.

Leading up to that year, Kosuga and an associate, Sam Siegel, purchased enough actual onions and contracts for future onion deliveries that they controlled 98 percent of the onions in the city — onions which were routed for delivery throughout the country. The duo had “cornered the market,” as they say, controlling the supply of a product and, therefore, its price.

After restricting the supply of onions and driving up their price, the duo flipped the trade. They purchased huge numbers of short contracts, or bets the prices would fall. And that, of course, is exactly what happened when Kosuga and Siegel flooded the market — a classic misdirection ploy. They made millions. Onions were so plentiful and cheap that stories abound of traders dumping them in the Chicago River, lest they have to pay to store them.

Outraged and recently impoverished, onion growers sought regulatory protection from speculators. A bill was proposed to ban futures trading in onions, which had become the most actively traded product at the exchange, says Scott H. Irwin, an economics professor at the University of Illinois who has studied commodities markets for decades.

Seeking to head off the bill and protect its business, the CME’s chairman testified before Congress.

“If there be abuses in (onion) futures trading, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange will be the first to condemn and correct” them, E.B. Harris testified, according to the book “The Futures” by financial journalist Emily Lambert.

Fast forward to the 60th anniversary of the infamous onion trade, and the CME Group finds itself in a similar predicament: fending off increasing regulation by promising to beef up its policing of a type of manipulative trading — this time, a modern-day misdirection ploy known as “spoofing.”

The policing effort has shown some success: CME Group says it issued 29 disciplinary actions for spoofing-like activity last year, up from 18 the year prior.

But the exchange also has its fair share of critics. At best, they argue CME Group could and should do more to spot spoofing, a tactic where traders attempt to influence prices to their benefit by placing orders they never intend to fill.

At worst, the critics say CME Group is paralyzed by a conflict of interest: It receives fees from the very traders it is being asked to put out of business.

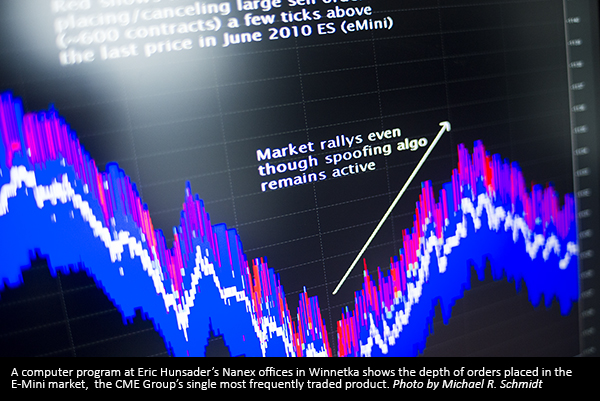

Eric Hunsader, who uses his technology firm, Nanex, to draw public attention to spoofing, says CME Group has not actively pursued spoofing “because the people they’ll issue the fines to are their largest customers.”

CME Group disputes this claim. It argues lax enforcement of its anti-spoofing rules would be against sound business judgment because it would undermine the market’s confidence in its exchange, leading to less business.

“No one has a more vested interest in protecting the integrity of our markets than CME Group,” Kathleen Cronin, CME Group general counsel, writes as part of a lengthy response to a list of questions from Chicago Lawyer.

In interviews with more than a dozen market participants — lawyers, professors and trading firm professionals — there is one thing everyone seems to agree on: CME Group is in the best position technologically to spot spoofing and put an end to it.

The disagreement begins when the next logical question is asked: How well is it doing the job?

A modern-day misdirection ploy

Spoofing is not a new phenomenon. But it has been supercharged by the same rise of technology that has emptied most of the city’s open-outcry trading pits. It is a computer-assisted tactic in which a trader (sometimes using a computer algorithm) profits by tricking others (typically computers) into believing the price of a futures contract is poised to move.

In one variation, the trick is accomplished by placing a large number of bids to buy contracts at a price above the current trading price. As the market sees that demand, the price moves toward it. Then, quicker than the blink of an eye, the spoofer cancels the large bids to buy contracts and places a similar or smaller-sized order to sell them. The sell orders are placed at the price the market has just risen to, allowing the seller to sell just a bit higher than it would have without the fake order.

And isn’t selling higher and buying lower what every trader wants to do? Of course.

One problem, though: The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act made trading in this manner explicitly illegal. Due to its history as the futures market capital of the world, Chicago has become the epicenter for the legal fight to end spoofing, technically defined as placing an order “without the intent to trade.”

In the biggest case to date, New Jersey-based trader Michael Coscia was convicted of six counts of commodities fraud and six counts of spoofing by a federal jury in Chicago in November — after just an hour of deliberation. On April 28, U.S. District Judge Harry Leinenweber is set to sentence Coscia. Each count of commodities fraud carries a maximum sentence of 25 years in prison and a $250,000 fine, the Department of Justice says in a release. Each count of spoofing carries a maximum 10-year sentence and a $1 million fine.

Unsatisfied with one victory, Zach Fardon, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, is attempting to extradite an alleged spoofer from London to face trial in Chicago. The Commodities Futures Trading Commission has also pursued civil cases against at least nine individuals.

These headline-grabbing cases have made spoofing the financial crime of the moment and, lawyers and trading-firm executives say, struck fear into traders. But spoofing has not gone away.

“If (traders) are entering a lot of orders without the intention to consummate, then they should go talk to their lawyers,” Timothy Massad, chairman of the CFTC, is quoted saying in a Reuters article.

Talk to the lawyers

Based on Massad’s advice, there are many traders who should be talking to their lawyers.

“There are dozens and dozens of trading firms in this town. Some are big, some small. Some registered, some not. They are all encountering some form of spoofing or another on a very regular basis,” says Cliff Histed, a partner at K&L Gates who has worked at the CFTC and as an assistant U.S. attorney.

The largest trading firm in Chicago, Ken Griffin’s Citadel Securities, began encountering what it would later recognize as spoofing in September 2013, according to a court filing. Their reaction and the ensuing investigation provides an example of the current regulatory environment.

A Citadel employee named Richard May noticed a decline in the firm’s trading performance in the market for E-Mini S&P 500 contracts in 2013. CME Group’s single most frequently traded product, E-Minis are a hedge for the future performance of the broad S&P 500 equities index. Citadel considers the E-Mini market a “critical benchmark and the most important pricing input for Citadel Securities’ futures and equities business,” May would later testify in a court affidavit.

May and a small team set out to determine the cause of their misfortune. They quickly realized they were getting caught on the wrong side of a spoofer. Within four months, May created a software program he refers to as a “pull-swipe detector,” using another, more literal term for spoofing.

A source familiar with the pull-swipe detector says it is “not as sophisticated as you might think.” It was an automated program that sifted through data provided by CME Group to spot a pattern where large orders were canceled and a similarly sized order was placed nearly instantaneously on the other side of the trade.

When a spoofer was detected in the market, May testified he would pull back Citadel’s trading by up to half, costing the firm “millions of dollars.” Citadel gave that information to the CFTC on Jan. 8, 2014, and to CME Group on Jan. 17, 2014. They would later be informed they had stumbled upon activity the CFTC and CME attributed to a trader — now well known — named Igor Oystacher.

Later in 2014, the CFTC had a lot of information on Oystacher.

Joy McCormack, a veteran CFTC investigator, testified in another court affidavit she had been investigating Oystacher since October 2011. By that time, McCormack testified the CFTC was aware of multiple complaints filed to the CME regarding Oystacher’s activity by market participants. By 2015, the CFTC knew of at least a dozen complaints.

In November 2014, CME Group fined Oystacher $150,000 and settled a disciplinary action against him by imposing a one-month trading ban. The trading activity identified in the CME’s report occurred in the copper and crude oil markets and dates from 2010 through 2011.

But an October 2015 lawsuit filed by the CFTC in federal court suggests Oystacher’s allegedly manipulative behavior occurred far more frequently than what is mentioned in CME Group’s disciplinary action. It shows Oystacher was active in the market for natural gas, the market for a gauge of market volatility known as the VIX and, as Citadel pointed out, the E-Mini market. The trading dates ranged from 2011 through 2015.

While his attorneys were defending against the CFTC’s initial complaint, the CFTC alleged in a February court filing Oystacher continued his spoofing practice. A trading firm alerted CME Group on Feb. 2 that it had to shut down its trading algorithms the prior day because of what it says was spoofing. A CFTC investigation, in partnership with CME Group, determined this activity again stemmed from Oystacher.

CME Group has issued no disciplinary actions related to spoofing-like activity this year. (View Chicago Lawyer's timeline of alleged spoofing on the CME from 2011 to 2015.)

Whose job is it anyway?

While it may seem difficult to catch (It all happens so fast!), there is broad agreement among experts that spotting instances of spoofing is a relatively simple endeavor for those closest to the market: high-frequency trading firms.

In order to be effective, spoofing must be noticed, says Craig Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston. It is designed as bait for high-frequency trading firms.

To a fast trader, the spoofer looks more like a sucker. A spoofer’s large bid to buy a contract at a price far away from the current one is an easy opportunity. In theory, it would allow a fast trader to purchase the contract at the current price — or even a bit higher — and quickly unload it to the spoofer at an even higher price. That is, until the spoofer flips the script and takes advantage of the heretofore unsuspecting HFT, as high-frequency traders are known.

“It’s sort of saying, ‘Look at me. Look at me,’” Pirrong says. “And it’s something that tends to be repeated. So those two things together do mean that companies like HFT firms … are likely to pick it up.”

Like Citadel, those firms have the resources to spot spoofing and can make the decision not to trade. Other traders are not so technologically savvy.

“These markets aren’t supposed to be HFT against HFT,” says one trading industry source who was not authorized to speak publicly. “Regular people are getting crushed by this.”

Market participants who would like to see improved oversight do not hold much hope the CFTC will provide it. The agency faces a number of challenges.

For one, it does not have access to real-time trading data from the exchanges, which makes it largely reliant upon others to open investigations. This lack of data was a cause of great concern for Mark Wetjen, a former commissioner of the CFTC. In a speech while he was still with the CFTC last year, he said, “The CFTC cannot retain the public’s trust in its ability to perform the agency’s congressionally mandated mission without the proper view of what’s occurring in the marketplace.”

Another former commissioner, Bart Chilton, shares similar doubts about the CFTC’s abilities. “The people at the regulators that look at the trading, they’re not physicists and mathematicians,” says Chilton, now a senior policy adviser at DLA Piper. “It takes them a while to figure this stuff out.”

Pirrong says, “The CFTC has a long-standing issue of being technologically challenged.”

The CFTC did not respond to an e-mail containing questions for this article.

These technological roadblocks suggest the responsibility to survey the market largely lies in the hands of one market participant: exchanges, like CME Group.

“They’re in the best position to detect this,” says Histed, the K&L Gates partner.

Says Hunsader: “Technologically, this is easy stuff to spot. Very easy. Especially when you’re the exchange.”

CME Group’s protocol

The main reason CME Group has the best ability to detect spoofing is because it is the only entity in the market that knows who is placing each order.

A trading firm may be able to notice a large pattern of canceled trades followed by orders on the other side of the trade. But the exchange can actually verify that one trader is behind both trades, which is a crucial step toward showing the trader never intended to execute the canceled orders.

In response to questions from Chicago Lawyer, CME Group says it invests millions of dollars each year in its market regulation function, including supporting and developing sophisticated technology. Its market regulation department has about 175 positions as well as tools to “query and aggregate real time and historical order messaging data at a rate of one billion rows per second.”

When that team spots trading it suspects may be spoofing, CME Group says it alerts the trader of the activity. If the activity persists — which the exchange says “almost universally” never happens — the exchange has the authority to “summarily deny access” to the markets.

There is only one instance where the exchange took this type of action, according to a review of disciplinary notices. In the cases of Nasim Salim and Heet Khara, the exchange says it noticed a pattern of disruptive trading in February last year. By April 30, the duo, who appeared to perform a kind of tag-team spoofing in the gold futures market, were denied access from the markets.

“Spoofing is prohibited in our markets and we have a number of procedures and systems in place to monitor for that and all disruptive trading practices,” CME Group general counsel Cronin says. “We proactively monitor the market for bad behavior and vigorously prosecute violations of our rules.”

Even though the disciplinary action for Salim and Khara appears to be exactly the type that many market participants are clamoring for, it was met with skepticism in some corners.

That’s because CME Group disciplined Salim and Khara two days after Hunsader, the founder of Nanex, posted a blog about specific instances of spoofing activity in the gold futures market — activity that occurred on the same day he published his post.

“It doesn’t take much effort to spot many HFT spoofing algorithms in real-time,” Hunsader wrote. “Here are three examples we easily found.”

A commenter on the widely read blog Zero Hedge, which picked up Hunsader’s story, wrote: “When will the CFTC and SEC get serious and hire Eric Hunsader? This guy is doing your damn job!!!”

In an unrelated case, Hunsader says he was given a $750,000 whistleblower award by the Securities and Exchange Commission for information that led to a $5 million fine against the New York Stock Exchange in 2012.

CME Group’s scorecard

In practice, CME Group’s disciplinary regime has a more spotty history than even the Salim and Khara case would suggest.

The CFTC issued a review of the CME’s abilities to detect spoofing from the period of July 2012 to June 2013. It found that only one of 10 spoofing investigations opened during that time originated from one of CME Group’s programs that detect spoofing-like trades. Eight investigations during that time were opened because of tips from trading firms. After the review period, the CFTC says findings from one of CME Group’s programs led to two additional investigations from that time period.

As a result of the review, the CFTC directed CME Group to find additional ways to detect spoofing. If it has, the programs work slowly.

Apart from the Salim and Khara actions, CME Group has exclusively disciplined traders whose spoofing-like activity happened more than a year ago, according to an analysis of the past two years’ worth of CME Group disciplinary actions.

That analysis identified 39 traders who were disciplined for spoofing-like trades. Only Salim and Khara were disciplined for trading activity that occurred last year.

A more typical example of CME Group’s disciplinary timeline comes from a trader like Aaron King, who received a $35,000 fine on May 29, 2015, for trades he placed from August to November 2011. Only one trader has received a permanent ban from trading: Nitin Gupta, who in July was also fined $150,000 for trading activity that occurred in 2013.

According to an analysis of CME Group’s disciplinary actions, there were 10 traders disciplined for spoofing-like trades placed in June 2013, a high-water mark for any month since 2011. By comparison, there were no alleged spoofers in 10 of 12 months last year.

CME Group says it has issued 47 disciplinary actions in the past two years related to spoofing-like behavior. Chicago Lawyer was able to identify 44 such actions. Some traders received multiple disciplinary actions.

While many people in the industry say the amount of spoofing has decreased, none of the more than a dozen sources interviewed for this article expressed an opinion that spoofing was not occurring this year or last.

As evidenced in the Oystacher case, this disciplinary time lag could allow alleged spoofing to continue. And in what may prove the most high-profile spoofing case, CME Group failed entirely to discipline the alleged trader: Navinder Sarao.

Navinder, Navinder, tsk, tsk

Sarao is a London-based trader who U.S. Attorney Fardon is fighting to have extradited to the States to face criminal charges in Chicago. The indictment and criminal complaint allege that from 2010 to 2014 he made more than $40 million using a specially designed software program that allegedly helped him conduct spoofing on a scale that dwarfs Oystacher.

The criminal complaint also says CME Group noticed Sarao placing and canceling orders that it says manipulated the opening price of futures markets as early as September 2008. On March 23, 2010, CME Group alerted Sarao’s clearing firm that he had 1,613 attempted trades rejected “in the last five minutes,” the complaint states. No actions appear to have come from this communication. About a month later, on April 27, 2010, Sarao is alleged to have made $821,389 in profits.

The complaint says CME Group reached out again on May 6, 2010 — the day of what is known as the “Flash Crash,” when stock markets globally fell nearly 10 percent in minutes before quickly recovering. In an e-mail referenced in the complaint, CME Group wrote to Sarao that all orders entered before the market opens “are expected to be entered in good faith for the purpose of executing bona fide transactions.”

Sarao responded 19 days later. The complaint says he wrote an e-mail to his clearing firm saying that he had “just called” CME Group. “Told ’em to kiss my ass,” he writes. He was arrested more than four years later by Scotland Yard. (Follow the efforts to spot and stop Sarao's alleged spoofing with this Chicago Lawyer timeline.)

Why did it take so long? Hunsader has a theory: “Sarao was a very high-volume customer, and that’s probably why they didn’t follow up.”

Does the math add up?

The Justice Department’s complaint against Sarao lists the volume of his trades for nine specific days spread from 2010 to 2014. During those nine days combined, Sarao traded more than 1.1 million contracts in the E-Minis market.

On average, his trades on those days made up more than 4 percent of the CME’s total volume in the E-Mini market. On Feb. 22, 2011, when he traded nearly 170,000 contracts, Sarao was a party to roughly 5.6 percent of all trades.

Sarao actively traded E-Mini contracts on 392 days from April 2010 to April 2014, the original criminal complaint says. He allegedly used the “dynamic layering technique” — a version of spoofing — on more than 246 days.

Sarao’s volume on the days detailed in the indictment would likely place him among the market’s most active participants on those days, according to a paper that analyzed real CFTC trading data from 2010 by Adam D. Clark-Joseph, a University of Illinois finance professor.

The data show the eight most active high-frequency traders in the E-Mini market accounted for roughly 1 million contracts traded each day. That would mean each of the eight traders, on average, traded 125,000 E-Mini contracts a day. Sarao traded more than 125,000 contracts on six of the nine days detailed in the criminal complaint. The most Sarao ever traded? 190,000.

But Clark-Joseph strongly rejects Hunsader’s theory that CME Group would be financially incentivized to turn a blind eye to Sarao’s trading. For one thing, Clark-Joseph says it is unlikely that Sarao’s trading activity was as high on the days not detailed in the complaint.

“One blip of 4 percent is really bizarre, but he was not 4 percent of the market for any sustained period,” says Clark-Joseph, who has studied volume data at the exchange but does not have first-hand knowledge of Sarao’s trading activity.

Furthermore, CME Group would take into account the adverse effect Sarao’s trades had on other market participants. For instance, Citadel, which says it is consistently among the top five most active traders in the E-Mini market, testified it reduced its trading volume by 50 percent on days in which it spotted spoofing activity.

“If other customers are getting ripped off, they’re less likely to trade,” says Pirrong from the University of Houston. “If this is really predatory activity, it’s not clear that the fees paid by the predators are going to be larger than the lost fees from those who decide not to trade.”

If other high-frequency traders’ reactions to spoofing are similar to Citadel’s, Clark-Joseph’s data shows how much that could cost CME Group.

He says the combined trading volume of the eight largest high-frequency traders for the E-Mini market is about 75 percent greater than the next 22 combined. And the 30 largest traders by trading volume make up about 10 times more volume than the next 300. And that comprises around 80 percent of the market.

“It’s pretty concentrated,” he says.

The E-Mini is the CME’s single most-traded product, making up 15 percent of all volume in 2014 — a year in which CME Group earned nearly $2.6 billion in clearing and transaction fees. Clark-Joseph says the trading breakdown is similar in about five other large markets.

“If I traded on the CME, I would not lose any sleep about spoofing,” Clark-Joseph says. “The people who have the best ability to catch it already have extremely strong incentives to prevent and discourage it.”

If that isn’t incentive enough for CME Group to enhance its policing activity for manipulative trading, there is always the cautionary tale provided by the fallout of Kosuga’s manipulation in the onions futures market.

“It caused this public perception that the markets were not fair and that prices were substantially manipulated and unwarranted relative to the true underlying fundamentals in the marketplace,” says Irwin, the U. of I. economist.

The bill to banish the onion trade was signed into law by President Dwight Eisenhower in August 1958. To this day, onions remain the lone agricultural product barred from trading in the futures markets.