At one point in time, the legal profession rested on a handful of bedrock principles: Stare decisis, centuries of case law, the Socratic method and the promise that if you master your craft, your name will be remembered.

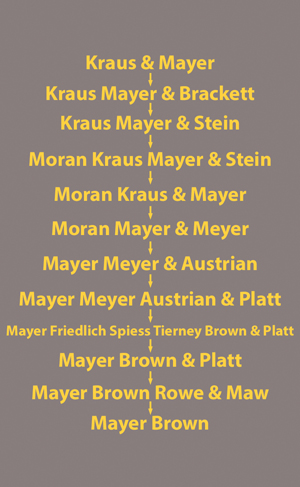

Sacrifice enough sleep, drink enough Manhattans to land enough big-name clients, bill more time than even your most harried partner and you could be the next Weymouth Kirkland or Howard Ellis (better known as Kirkland & Ellis), Levy Mayer (of Mayer Brown lore), Albert Jenner (you guessed it) or any other legal legend now memorialized in their law firm’s name.

But your name better have landed in the first two spots of that sequence, lest you end up on the chopping block like John Rowe and Frederick James Maw (of the former Mayer Brown Rowe & Maw).

And what about the “SNR” trio? They fell out of fortune when SNR Denton, like so many other law firms, took to perfecting that two-name-or-less, no-more-than-four-syllable art form: the common-day law firm name.

Did anybody stop to think how Edward Sonnenschein’s, Bernard Nath’s or Samuel Rosenthal’s families felt?

All kidding aside, the law firm branding machine spares no attorney as it rolls on — slowly, surely, quintessentially legal — reducing legacies to word-of-mouth preservation.

Today, of course, there is no promise to lawyers at the largest firms that with hard work, sweat and equity, their name will be synonymous with their firm’s reputation long after death. Consider it another lowered expectation for today’s law school graduates.

But the dream of having your name in lights, it turns out, was a historical anomaly.

Having your name eternally (or at least more than temporarily) enshrined in marble, on business cards or in a general counsel’s Rolodex was an opportunity available mostly to a generation or two of lawyers who dominated their firms somewhere after 1945 but before the 1970s — with some exceptions.

That’s the timeframe when law firm names — historically prone to a morbid sort of musical chairs — began to set in stone, thanks to the profession’s evolving ethics. Today, the staid hierarchy is under attack by an innovative group of business-minded attorneys with a radical plan: Get rid of the human history in law firm names.

Your name or the highway

At least in Chicago, one of the legal profession’s most basic, overlooked and oddly regulated traditions can be traced back to 1859.

Two years before the Civil War, Stephen A. Goodwin, Edwin C. Larned and Daniel Goodwin Jr. began practicing law together. Their firm was called Goodwin Larned & Goodwin because, well, what else would it be called?

Today, it’s known as Fitch Even Tabin & Flannery, a roughly 55-lawyer intellectual property firm which also calls itself the oldest contiguous law firm in Chicago, dating back to 1847.

In Fitch Even’s early days (yes, Tabin and Flannery are dropped when the firm refers to itself), law firm names were not a brand. They represented a personal reputation, and the names changed as major partners either left the firm or died.

In Fitch Even’s early days (yes, Tabin and Flannery are dropped when the firm refers to itself), law firm names were not a brand. They represented a personal reputation, and the names changed as major partners either left the firm or died.

Thomas P. Sullivan remembers those days. The senior partner at Jenner & Block (the 10th derivation of a firm originally known as Newman Poppenhusen & Stern), Sullivan joined the firm in 1954 when it was Johnston Thompson Raymond & Mayer. People were then calling it the “Thompson firm,” previously known as “the Poppenhusen firm.” Either way, those wouldn’t last.

“In those days, it was considered unprofessional to use the name of a deceased partner, so they always changed it, with very few exceptions,” Sullivan said.

Why?

“You were profiting on the reputation of a different person. And that was unprofessional,” he said. “It wasn’t grounds for disbarment, but it was looked down upon. As soon as this person died, after a decent interval, they would change the name.”

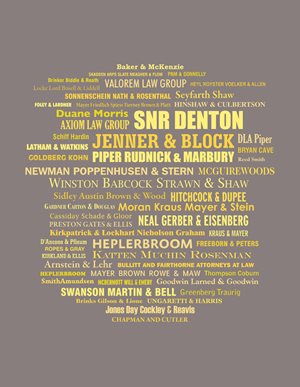

That can be seen in the name-changing histories of almost any large Chicago firm.

Winston & Strawn, which dates back to Frederick H. Winston’s self-titled practice in 1853, has gone by 24 names. During a 20-year span from 1889 to 1909, the firm went by five different titles, which were actually a combination of six people’s last names. There are multiple Winstons in the firm’s history.

Schiff Hardin — its roots planted in 1864 as Hitchcock & Dupee — has gone by 20 names, all various amalgamations of a total of 22 (presumably) standout partners.

Mayer Brown was founded as Kraus & Mayer in 1881 by Adolf Kraus and Levy Mayer. Mayer may very well hold the postmortem distinction of being the longest-running name partner in Chicago law firm history.

One of the wealthiest and most powerful lawyers in the country, he died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage in 1922. Time magazine said his estate at the time of his death was valued at $8.5 million — roughly $115 million today.

The guy was the tops. And that is where he’s stayed.

It’s likely that Mayer’s name was kept due to his outsize influence and his untimely death. That was an exception in 1922, again when it was still considered unprofessional for a firm to use a deceased partners’ name.

An ethics study

Lawyers such as Tom Luning, a former managing partner of Schiff Hardin who joined the firm in 1968, know that names didn’t outlast people very often.

“It may even have been that there were ethics opinions that said that was improper to do,” Luning said. “Because it sent a message to the public that there was a lawyer there who wasn’t there.”

Luning can’t say for sure where the prohibition originated. Neither can Chicago Lawyer’s thorough but admittedly inconclusive research of the history of legal ethics.

Indeed, it is unclear if law firms were ever expressly prohibited by the American Bar Association or another professional ethics body from using the names of deceased partners.

The first code of ethics that lawyers adopted in the United States appeared in Alabama in 1887. The Alabama Code of Ethics was authored by Thomas Goode Jones, a governor who supported segregation during his gubernatorial race but was simultaneously friends with Booker T. Washington, according to the Alabama Humanities Foundation.

The Code of Ethics adopted by the Alabama State Bar Association included 57 codes or rules. None make mention of how law firms should name themselves. In fact, they don’t mention law firms at all.

Carol Rice Andrews, a professor at the University of Alabama School of Law, confirmed that law firms existed at that time, but she pointed out that they were usually small partnerships. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, practiced with Stephen Logan from 1843 to 1844 and William Herndon from 1844 to 1852 — more than 40 years before Alabama’s code foreshadowed a national ethics sweep.

The American Bar Association in 1908 passed its Canon of Ethics, which closely mirrors the Alabama guidelines and, again, provides no guidance for naming a law firm.

So where did the rule come from?

The first time the ABA addresses the issue is to say that using deceased partners’ names is, in fact, OK. Which, of course, leads one to assume it was once not OK. Or at least lawyers had enough questions about it that the ABA decided to answer them.

The 1928 Canon 33 of the ABA Canon of Ethics says in part: “No false, assumed or trade name should be used to disguise the practitioner or his partnership. The continued use of the name of a deceased or former partner is or may be permissible by local custom, but care should be taken that no imposition or deception is practiced through this use.”

In 1937, that canon was amended to explicitly state that using a deceased partner’s name “is not unethical.”

The ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility, adopted in 1969, says in disciplinary rule 2-102(B): “If otherwise lawful a firm may use as, or continue to include in its name, the name or names of one or more deceased or retired members of the firm or of a predecessor firm in a continuing line of succession.”

The Illinois State Bar Association relied on this rule in November 1980 when it issued an ethics opinion — in case lawyers needed an even lower risk threshold — to say: “It is professionally proper for a law firm’s name to contain the name of a deceased member of the firm.”

Today, the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct make no reference to whether or how deceased partners’ names should be used in a firm name.

Whichever opinion your particular law firm relied on to turn its former partners’ surnames into brand names, few if any law firms still play the revolving name game. Now, they stick with names of long-deceased partners.

Which begs the question: Who were the lucky former partners sitting down when the music stopped?

How Fitch got Even

Fitch Even makes for a good case study.

It has gone by 19 names in its 167-year history, beginning when Edwin Larned practiced under his own name.

It has gone by 19 names in its 167-year history, beginning when Edwin Larned practiced under his own name.

Morgan L. Fitch Jr. wasn’t added to the firm’s nameplate until 1956 — eight years after joining Soans, Pond & Anderson. Fitch was the perfect age to be memorialized, and he had the legal chops to fulfill that promise, said Tim Levstik, who joined what was known as Fitch Even & Tabin in 1980 and worked with all three of those partners. He managed the firm for roughly a decade.

“Morgan was a skilled patent lawyer and had the ability to attract clients from all over town — even though he was, frankly, kind of a common-looking guy,” Levstik said. “There was no big pretense about Morgan. Not at all. If you saw him, why, you might have given him a few bucks to find his court coat.”

The appeal of having your name as part of the firm is what some lawyers are in the gig for in the first place: “It gave them a little more prestige or clout to be in the firm name,” Levstik said.

Fran Even likely played a convincing foil to Morgan.

Even was about 6-foot-4 and cut a very imposing figure, Levstik said. He wore nice clothes, in contrast with Fitch, and his upright posture made him seem like a general in service to his country. That made sense, considering that Even, like all of the name partners, played a part in World War II. He served as a combat engineer.

“He was shot at probably more than” any of the name partners, Levstik said. “Fitch was on board a small aircraft carrier, and he survived at least one kamikaze attack.”

Julius Tabin’s background was even more outlandish, and he exemplifies the variety of personalities that could climb the law firm ranks and splash their name across the letterhead.

Tabin, who had a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Chicago, was underneath the school’s football stadium when his colleague Enrico Fermi oversaw the first test of a nuclear reactor there. He later was among the original group of scientists to take soil samples from the first test of the atomic bomb at the Trinity site in New Mexico in 1952.

“Fitch, Even and Tabin really took control of the administration of the firm in the early ’50s after the war,” Levstik said. “I think because of their experiences, they weren’t afraid very much of anything.”

Is it their patriotic characteristics and impressive legal smarts that made them long-lasting stewards of the firm’s goodwill?

Not quite. If anything, Levstik said he’s the reason the firm’s name hasn’t changed.

“We just institutionalized the name,” he said. “Does McDonald’s change the color of its arches every 10 years? No. And rather than have the name change every five years, we’ve just institutionalized the name. And certainly Fitch, Even, Tabin and Flannery were happy over that.

“Also, it’s sort of chic now, I suppose, in marketing circles, to have Fitch Even — one (brand) name firm for the marketing and logo.”

There you have it. The name formed in 1983 has stuck. And it’s not moving.

“There’s been absolutely no movement created by egos or otherwise to have somebody’s name put in the firm name,” Levstik said. “Zero.”

Two-name hegemony

On its own, the concept of law firms using partners’ names as brands makes it difficult to differentiate one from another.

The names don’t express something about the firm the way a corporate brand might. Everybody knows what Kraft Foods does. It would take some industry knowledge to know that Kirkland & Ellis, Jones Day or Skadden are some of the best law firms to guide you through a corporate merger.

Some lawyers or consultants may say that’s irrelevant. In-the-know professionals, and not everyday consumers, are purchasing their services. Regardless, the marketing pros are aligned that the answer to market confusion is a shorter name.

Consider Piper Rudnick & Marbury’s 2002 decision to scrub off Marbury.

Francis B. Burch Jr., then-co-chair of the firm, told the Baltimore Business Journal that the change was made to “shorten the name of the firm and give it a more unified look.”

“All of the market research and all the pros tell you that your typical audience can digest two or three syllables, and the rest is lost,” Burch said. “There’s some confusion out there in the marketplace.”

Today, law firms shy away from talking openly about the rationale behind name changes, which have only accelerated due to high-profile legal mergers.

Allen C. Chichester, Piper Rudnick’s chief marketing officer when the change occurred, did not return a request for comment.

K&L Gates also declined to provide insight on how it arrived at its hybrid moniker.

The firm’s current name is the result of a 2006 merger between Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham and Preston Gates & Ellis. William H. Gates Sr. — who joined the firm in 1990 and is the father of Microsoft founder Bill Gates — was the only name to survive the merger intact. That’s despite Harold Preston being the founder of the firm in 1883.

Perhaps K&L Preston was too many syllables. Maybe the father of the richest man in the world had more name recognition than a lawyer born in 1858. It’s hard to say for certain. What is clear is that K&L Gates bucked tradition in two ways: It used initials, and it scrapped the first name of a predecessor firm while keeping that same firm’s second name.

Sixty percent of law firms in this year’s Chicago Lawyer survey series have two surnames in their “brand name.” But shortening law firm brands (that’s what they are now) to one or two names provides little in the way of clarity around the actual work they do.

Nor does it answer how firms approach other purely scholastic debates. For instance: Comma or no comma? Does a space between names accurately reflect the brand? Or should there be no space?

Asked about the decision to go without a space, a SmithAmundsen spokeswoman said: “There’s no story behind it. It’s just a decision we made.”

Duane Morris does not use a comma. But don’t mistake the Philadelphia firm started by Russell Duane and Roland Morris for a person, even though that often happens to a firm who sounds like it could be a first and last name.

Duane Morris, a now-deceased partner at Buckingham Doolittle and Burroughs in Akron, Ohio, had to live with that confusion for his 54-year career, said John Soroko, chairman of Duane Morris, the 100-year-old law firm, who met the man years ago.

“Every time he introduced himself, people would say, ‘So you’re calling from Philadelphia?’ He would say, ‘I’m an individual person, a man named Duane Morris with an Akron law firm,’” Soroko said.

“He told me almost every introduction he had to make in his entire legal career for 40-plus years had been encumbered by needing to make this introduction.”

As for the rationale for not using a comma, Soroko said it’s simply a waste of ink.

“From an advertising and branding standpoint, punctuation is considered surplusage or an unwelcome distraction,” he said. “And you just go with the name, or the two names, no punctuation.”

No name, no gimmicks

But some lawyers are now considering human names to be brand baggage.

Axiom Law Group, a non-partnership which considers itself a disruptive innovator in the legal industry, has a name that Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as a maxim widely accepted on its intrinsic merit.

That maxim, in Axiom’s eyes, may be that the law is ripe for a shake-up.

Another firm that believes in shaking up the legal landscape is Valorem Law Group, co-founded by Patrick Lamb.

Valorem is not a person, Lamb said. It’s Latin for “value” and is a reference to a unique aspect of the firm’s billing method: Every bill contains a value-added adjustment line.

“We invite the client to adjust the fee — either up or down — to an amount that reflects the value we provided,” Lamb said. “That leaves the ultimate determination of the value in the client’s hand.”

The firm, founded in 2008, has included that in every invoice it has ever sent out. Only once has that led to a problem. Early in a case, a client refused to pay a bill. Valorem asked where to send the case file, scrapping the professional relationship.

Lamb had that billing method in mind when he started the firm, and a group of founders sought out a name that would reflect the radical change their business model represents from a typical law firm. They tossed out names that had to do with the solar system — ideas such as “Galactic Law Group” that evoked big ideas.

That was something different, but it didn’t really speak to what the firm was trying to do. So the lawyers shifted to thinking about how to express their business proposition in a word. A colleague who has since left the firm landed on Valorem.

“It’s memorable because it’s not Smith, Jones and Aronsen or whatever,” Lamb said. “And it’s short. It sticks in people’s minds.”

Those are good attributes to strive for the next time management wants to lop off another legacy.